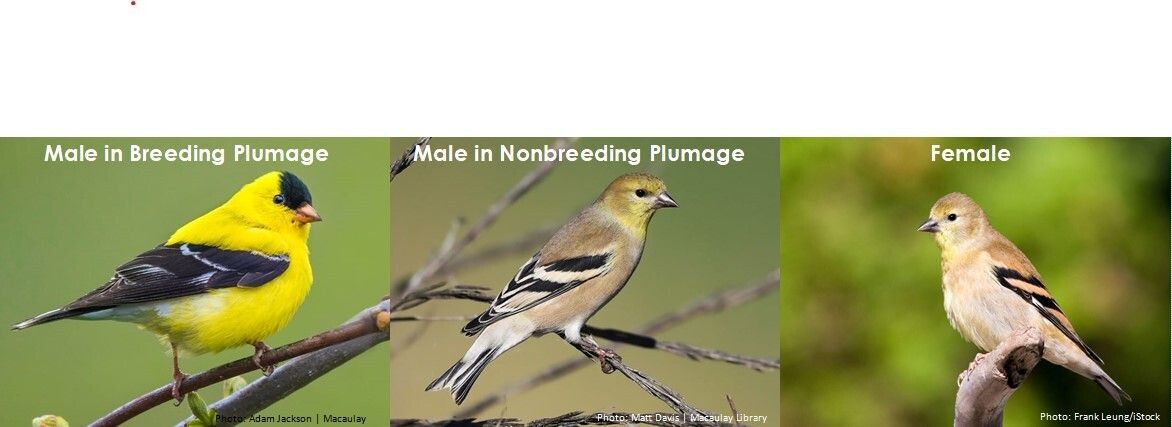

In 1933, the American Goldfinch, Spinus tristis, was named Iowa’s state bird. Easy to identify with its bright yellow body and contrasting black and white wing markings, this little seed-eating bird is many a birdwatcher’s favorite visitor to backyard feeders. Around this time of year, however, people begin asking, “Where did all my Goldfinches go?”

Chances are, they are still here, although you may not recognize them disguised in their winter garb.

For many bird species, including the American Goldfinch, it is the male that sports the bright plumage to attract the attention of females. Females, on the other hand, are usually a more drab, gray or brown color to make them inconspicuous to predators while spending large amounts of time incubating eggs and brooding young. All birds undergo a yearly molt where they shed their old, worn feathers and grow fresh new ones. For many bird species, this molt occurs in the fall, after the breeding season. Because there is no need to draw the attention of females in the fall and winter, male Goldfinches lose their bright breeding plumage for more practical gray-brown winter attire. Come spring, the male Goldfinch will undergo a second molt and begin donning the brilliant gold color for which these little birds are named. The Goldfinch is the only one in the Finch family to perform this biannual molt.

If you want to attract Goldfinches this winter, here are a few things to consider: Sunflower, Nyjer, and thistle seeds are Goldfinch favorites. Although they are not particular about the kind of feeder used, Goldfinches are wary of larger birds. Using tube feeders with small perches where larger, more aggressive birds can’t feed will increase the likelihood of drawing Goldfinches. Sock feeders work well for Nyjer and thistle seed. Place Goldfinch feeders a good distance away from other feeders, keep seeds dry, replace uneaten food every three to four weeks, and clean up spillage from the ground. Goldfinches won’t feed on dried-out seed, so buy smaller amounts more often or store your seed in the freezer to keep it fresh.

While experts agree it’s not a good idea to provide supplemental food to wildlife in general, song birds are the exception. If good practices are followed, research shows that feeding songbirds benefits our wild, feathered friends. It benefits us as well. The company of birds brings a lot of joy during the long winter months, and maintaining feeders engages people in our natural world, fostering a sense of purpose and belonging.

If you enjoy watching birds at a feeder, you can contribute to the scientific study of birds through Project FeederWatch, a winter-long citizen science project where participants periodically count the birds they see at their feeders and report their observations. You can count birds as often or as infrequently as you like. The information helps scientists track long-term trends in bird distribution and abundance. Interested? Check it out at feederwatch.org.